Inside Mars's Retail Media Investment Matrix

Major CPG brands are building formal evaluation frameworks to decide which RMNs deserve budget. But here's the downer: even when networks make the cut on paper, it may not translate to media spend.

At the Path to Purchase Institute LIVE conference last week, Kelly Spehar stood on stage and described something most retail media networks would rather not hear: Mars' snacks business has built a formal scorecard to decide which networks get budget and which don't.

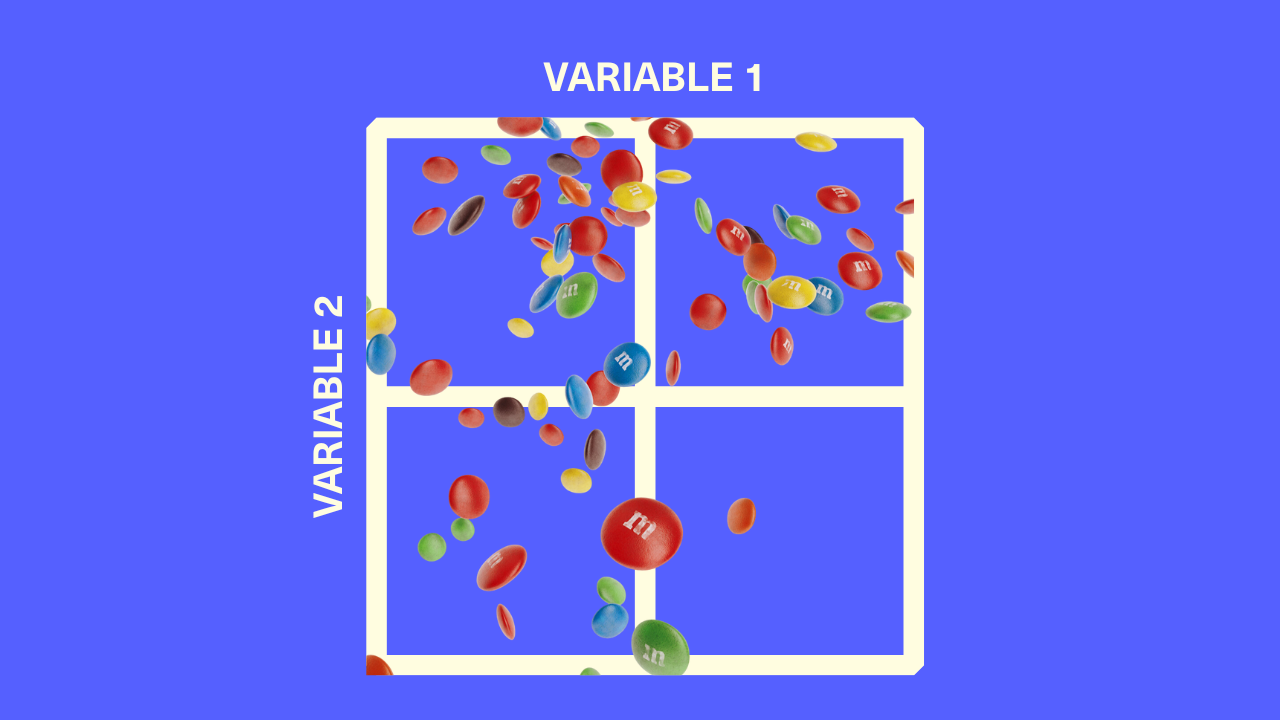

"We've created what we're calling an investments matrix," Spehar, Mars's Global Retail Media Strategy Director, told the audience. The matrix evaluates networks on two dimensions: retailer media capabilities (audience targeting, reporting, all the features offered) and commercial growth (partnership sales, net sales value, future growth potential).

The output is a ranked list of retailers for each region, complete with tactical guidance. Start with search. Expand to on-site display. Then off-site display. Maybe CTV eventually. "We found that super beneficial," Spehar said. "Just a guide on how and where to invest, which has been a big piece of work."

This is what accountability looks like when it moves from theory to practice. And Mars isn't alone.

The Case For An RMN Scorecard

The Association of National Advertisers recently released guidance recommending exactly this approach. In their September 2025 "Retail Media Internal Management Guidance" report, the ANA tells brands to "implement a scorecard framework that evaluates retail media networks based on business goals, account size, brand growth, past performance, or platform capabilities, ensuring funding decisions are based on objective standards rather than reactive spending or sales-led pressure."

The report, developed with input from 17 major CPG brands including Brother, Clorox, Colgate-Palmolive, Hershey, Kimberly-Clark, Kraft Heinz, and PepsiCo, identifies fragmented budgets and lack of clear accountability as core problems. Without structured evaluation, sales teams overcommit to retailers during joint business planning, marketing teams get stuck executing strategies they didn't shape, and nobody can prove which networks actually deliver.

The scorecard approach addresses a genuine problem: turning ad spending from a sales negotiation into a performance conversation. But there's an uncomfortable truth underneath all this structure.

A Hard Ceiling On Growth

A couple of months back, I spoke with a senior retail media buyer at a multinational CPG conglomerate who's built exactly the kind of scorecard the ANA recommends. Their framework evaluates networks on scale, capabilities, incremental ROAS, growth trajectory, total store performance, and online share growth. They've set a capabilities floor—no new networks get consideration unless they clear minimum standards.

But here's the rub: when I asked whether they'd expand beyond their current 5-6 retail media relationships if more networks suddenly met their standards tomorrow, the answer was immediate. "No. The revenue contribution isn't there. The juice isn't worth the squeeze managing an additional relationship."

Despite all the complaints from brands, this isn't about retailers failing to perform. Some networks on their scorecard actually pass the capability requirements. The constraint is operational capacity – on the brands' side.

The average brand works with six retail media networks. That number hasn't budged even as dozens of networks have launched and matured. The ANA report documents why: "Managing multiple retail media networks requires significant time and effort, often overburdening internal teams already stretched thin with other responsibilities."

Even Mars, with its sophisticated matrix and regional guidance, isn't signaling plans to dramatically expand the number of networks they activate against. The matrix helps them optimize allocation and provide clear direction to regional teams—but it's fundamentally a tool for managing existing relationships more strategically, not for scaling to 15 or 20 partners.

This ceiling on the number of networks a brand is willing to work directly with is a ceiling on the growth potential of retail media as a whole. Several solutions have been proposed to solve this supply and demand gap, including retail media consortiums and Real Time Bidding.

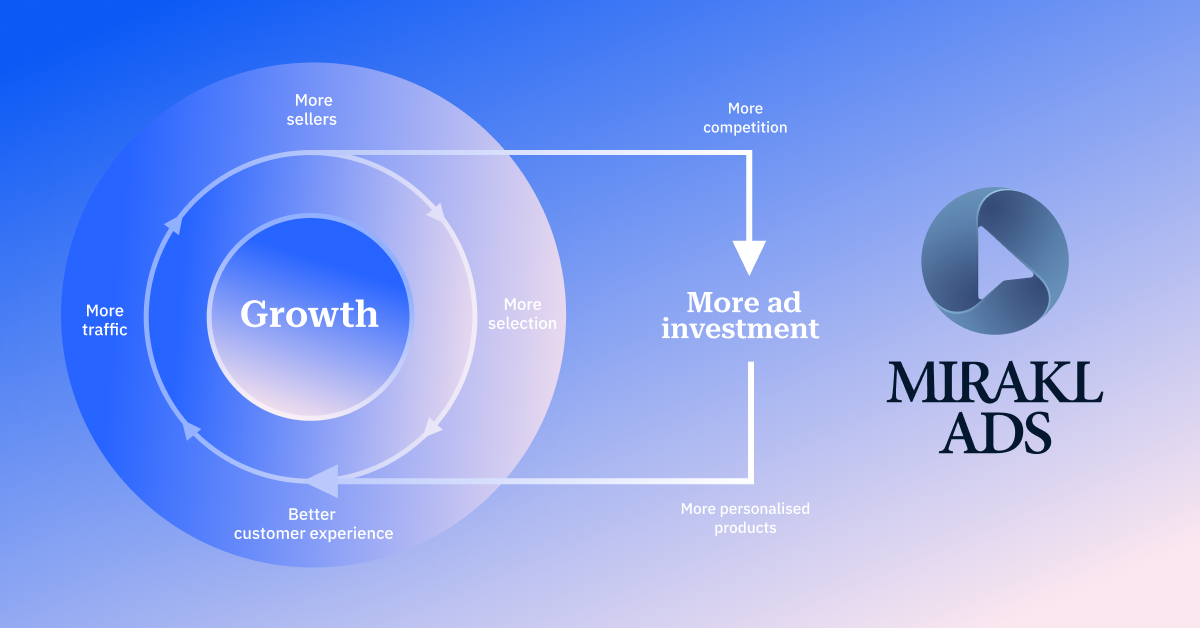

Mirakl Ads is the only retail media solution designed for both 1P & 3P marketplace brands. Why does that matter?

Marketplace sellers demand a seamless advertiser experience that still offers full-funnel ad formats. And retailers need a flexible solution that allows you to scale your media business.

Why Brands Cap Their RMN Relationships

The operational burden breaks down into several categories, all of which compound as you add networks:

Platform fragmentation. The anonymous CPG media buyer I spoke with is pushing for self-serve access wherever possible—"we want to layer into Meta, layer into DV360"—specifically because managed service creates control and brand safety concerns. But self-serve means logging into different platforms, learning different interfaces, and navigating different reporting structures. Even with consolidated dashboards, each network requires dedicated attention.

Measurement inconsistency. Ben Galvin, Senior Director of eCommerce & Omnichannel Retail Sales at Monster Energy, said on the same panel at P2PI Live that measurement is still very fragmented. every network measures it differently. Some run holdout tests. Others use synthetic controls. Attribution windows vary. Definitions of "incremental" shift. "There's no uniformity in measurement and dashboards across retailers, and that continues to be a challenge."

Relationship management. Brands are increasingly pushing for merchants to be brought into retail media conversations. I've heard that retailers who bring merchants to the table are given a strong preference by brands. Indeed, some retailers like Ahold Delhaize are leaning into this model.

Commercial negotiation complexity. Every network has different commercial terms, different budget structures, different expectations around joint business planning commitments. Multiply that by 15 networks and you've created a full-time job just mapping and managing the commercial relationships.

The Rich Get Richer

Here's what scorecards actually do: They formalize which incumbent networks keep their budget and which ones get cut. They don't create expansion opportunities for mid-tier networks—they create a performance bar that protects the top six.

I've heard from media buyers at 2 separate CPG conglomerates who show their RMN partners blind competitive data: something like, "Here's where you sit on iROAS compared to other networks we work with." On one hand, that transparency creates accountability. Retailers know they're being evaluated against peers. But it doesn't open slots for new entrants.

Emerging retail media networks can invest in better measurement, improve targeting capabilities, build self-serve platforms, and still not crack the top six because they're not displacing enough revenue to justify the operational burden.

Going Smaller To Go Bigger

This “hard ceiling” applies mostly to the largest advertisers — the ones with the power to demand custom measurement, negotiate JBPs, and build scorecards that effectively freeze out mid-tier networks.

But it doesn’t apply to marketplace sellers.

A new Forrester Consulting study (commissioned by the sponsor of this newsletter, Mirakl Ads) found that 3P sellers don’t hit the same RMN budget caps at all. In fact, 63% of retailers say retail media demand has increased specifically because marketplace sellers are now participating.

Why? Because marketplace advertisers operate under an entirely different logic. They’re not managing 15 retail partners, they’re not building capabilities scorecards; they simply spend when ads help them sell more.

That means marketplace retail media sidesteps the operational ceiling constraining big-brand budgets and opens access to a much broader, more scalable demand pool. This is the model that the largest online retailers – Amazon, Walmart, Target, and others – have pursued, tapping into thousands of sellers who aren’t limited by the brand-driven scorecard logic that constrains traditional RMNs.

The challenge, of course, is volume. It takes a lot of individual sellers to equal one large brand advertiser.

Now What

Scorecards can solve real problems. They bring data discipline to budget conversations. They give marketing teams ammunition when sales wants to overcommit to a retailer. They force networks to prove incremental value rather than relying on relationship momentum.

But they don't solve the fragmentation problem the industry keeps talking about. If anything, they formalize it.

Mid-tier retail media networks hoping to break into the top six need to understand they're not competing on capabilities alone. They're competing for displacement. That means either:

- Growing their retail partner's business so significantly that the brand can't ignore the revenue contribution

- Offering such superior measurement or targeting capabilities that they justify the operational burden of onboarding

- Tap into the long tail of smaller sellers and brands

- Making integration so seamless that they reduce rather than increase complexity

The last path is promising, and we're seeing moves like Best Buy positioning itself as ad infrastructure for other retailers, or the idea of federations and consortiums, even Real Time Bidding making a play for a second act in retail media. If mid-tier networks can plug into existing workflows rather than requiring separate management, the operational ceiling lifts.

But for now, most large brands are doing exactly what Mars described: building matrices to optimize allocation across a fixed set of partners. The scorecards are coming—not to expand the playing field, but to defend it.

The ANA's "Retail Media Internal Management Guidance" is available at ana.net.