Agentic Shopping Might Seem Crazy. So Did Self-Service Supermarkets.

History is littered with technologies that never escaped the hype cycle. But some innovations that became mainstream also looked absurd at the time.

Memphis, Tennessee, 1916. Clarence Saunders is about to do something that everyone thinks is completely insane.

For decades, grocery shopping worked the same way: you handed your list to a clerk who fetched your items from behind the counter. But having someone wait on you wasn't as convenient as it sounds. Clerks short-weighed products, slipped in spoiled produce, and customers had to wait around for chatty Cathies ahead of them in the queue. The clerk would scribble your total on the back of a paper sack, and add it to a credit account that was floated by the store. The system was inefficient and often corrupt, but it was all anyone knew.

Then there was Albert Bowers, who ran a "penny store" that eliminated charge accounts and insisted on cash only. Everyone thought he was mad. Yet his lean operation created a cost advantage that built customer loyalty. Working for Bowers, Saunders absorbed these lessons and prepared to push them further.

Saunders asked a question that seemed heretical: Why do shoppers with lists need clerks at all?

His answer was Piggly Wiggly—the first self-service supermarket. He patented a one-way aisle system that forced customers to snake through the store. He charged three cents for baskets. No clerks. No deliveries. No phone orders. Critics mocked the silly name and the absurd idea of customers waiting on themselves.

To make it work, Saunders introduced tools that seem obvious now but were revolutionary then: standardized price tags that eliminated haggling, adding machine tape that printed receipts, and customer-facing scales. These innovations created transparency and trust—essential ingredients for any disruptive model.

Piggly Wiggly exploded from one Memphis store in 1916 to 393 locations just 3 years later. A&P, the biggest grocer at the time with 4,000 stores, was forced to abandon the clerk model and copy Saunders' self-service approach.

The lesson isn't that Piggly Wiggly conquered the world. (Managerial missteps later sank the company.) The lesson is that the future never arrives by consumer request. Shoppers in 1916 didn't demand self-service. They didn't even know they wanted it. It came from someone reimagining inefficiencies that everyone else had learned to tolerate.

When your time, budget and team are already maxed out, keeping up with retailer platforms and media requirements can feel like a never-ending labyrinth. That’s why even the best brands bring in an execution partner.

Acosta Group makes retail media execution simpler. They stay ahead of every platform update, tech shift, and media spec. So your campaigns actually show up and perform—without draining your team.

Cherry-Picking Retail Failures... And Successes

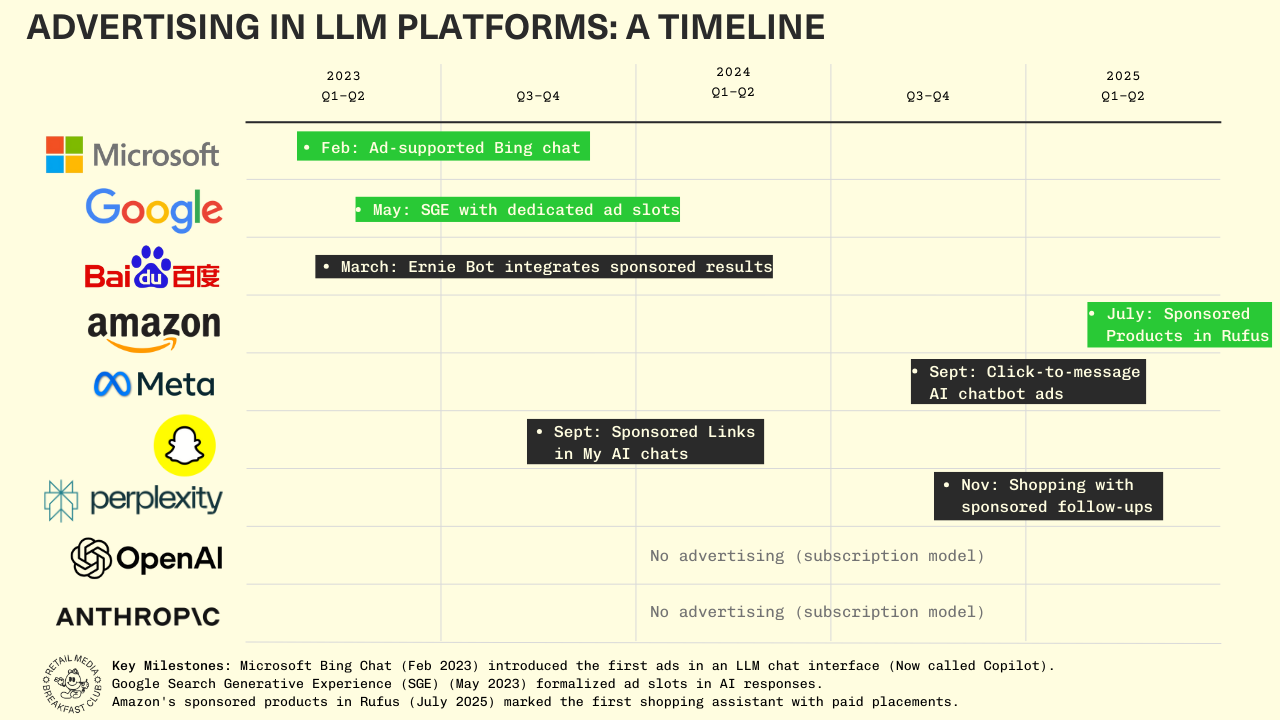

Andrew Lipsman, a retail analyst I deeply respect (and have debated with over drinks more than once), makes a thoughtful case for caution around agentic commerce in his essay, Agentic Commerce is a Collective Hallucination, where he points to a pattern: Voice Commerce (2018), Metaverse Commerce (2022), Livestreaming Commerce (2019), Shoppable TV (2016), IoT Commerce (2016). Each promised to revolutionize how people shop. Each generated breathless hype. And each ultimately proved inconsequential to the broader retail landscape.

(Andrew made several other arguments in that piece that dismiss widespread use of agentic commerce, but I'm addressing just this one today.)

His point is valid. The retail industry has a well-documented habit of chasing shiny objects, declaring each new technology "transformative" before moving on when adoption stalls. Given this track record, skepticism about AI shopping agents isn't just reasonable—it's prudent.

But here's where I think the skeptical view risks missing something important: it treats all "failed" innovations as equal, when history suggests some supposed failures were actually just too early.

Webvan.

Webvan tried grocery delivery in 2000 with automated warehouses and its own fleet. It scaled too fast, burned cash, and collapsed—cementing the belief that "people don't want grocery delivery." Except Webvan got the economics wrong, not the vision. Twenty years later, Instacart and DoorDash used asset-light marketplace models instead of building expensive infrastructure. By 2024, DoorDash held 61% U.S. delivery share.

Amazon.com

Amazon.com launched in 1995 as an online bookstore. By 1999, Barron's ran a cover story titled "Amazon.bomb," predicting doom. Early detractors argued it "wasn't a bookstore at all"—just a broker. But compounding improvements—massive selection, reviews, Prime logistics—removed friction and built new habits. What started as a niche use case (books) became the default way to buy nearly anything.

Social commerce

Meta removed Instagram's Shop tab and ended live shopping features, fueling the view that "people don't want to buy inside social apps."

Then TikTok Shop launched in September 2023 with embedded checkout, creator affiliate videos, and fulfillment support—making shopping feel like a natural extension of the For You feed. The product found fit where Instagram couldn't. By late 2024, TikTok added roughly 12M U.S. social buyers, with monthly GMV topping $1B. Multiple trackers peg U.S. GMV in 2024 in the high single-digit billions, with continued growth into 2025.

Each "failure" the skeptics cite reveals a pattern: early versions expose real consumer needs, but wrong execution or missing technology prevents mainstream adoption. When the model recombines with the right tech stack—mobile plus marketplaces for delivery; checkout embeds for BNPL; UX refinement for Amazon; creator-driven in-feed commerce for TikTok—suddenly the "irrational" idea becomes obvious.

Musical.ly Became TikTok. And Agentic Shopping Will Evolve Too.

Musical.ly was dismissed as a teen gimmick from 2014-2017. Then it became TikTok. Algorithm-driven discovery, polished editing tools, broader creative formats. Short-form video wasn't niche anymore—it became the global content format. The use cases explode once the product matures and the tech expands. What looked narrow and gimmicky became a cultural default.

Today's agentic shopping experiences are clunky, limited, and frankly ugly. I'll be the first to admit that. But everyone can agree that the technology is nascent. We're still in the early innings.

I anticipate additive shopping experiences like persistent preferences, shopping companions, and AR try-ons which could create entirely new shopping experiences and behaviors, but the truth is we haven't seen what this technology is fully capable of yet.

Could agentic shopping end up like voice commerce—a feature that finds niche use cases but never becomes a primary shopping interface? Absolutely. Skeptics like Andrew might be completely right that we're watching another overhyped cycle.

But here's my concern about dismissing it out of hand: we're making predictions about consumer behavior based on technology that's still evolving rapidly. The agents we're testing today will look as primitive in three years as Musical.ly looks compared to TikTok.

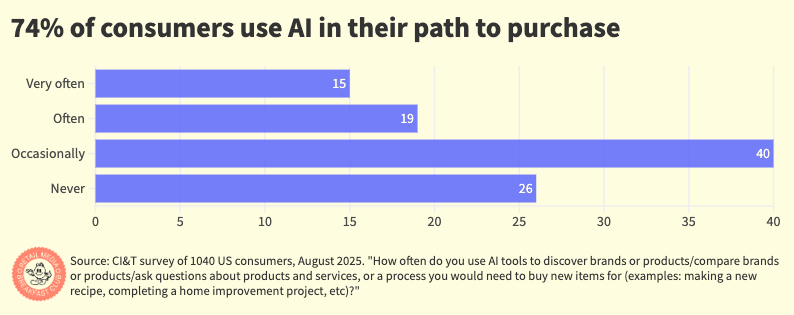

Consumer surveys (which admittedly should be taken as directional at best) find that consumers are generally interested in the idea of agentic shopping, particularly in more mundane categories like grocery shopping – but also in 'fun' categories like apparel.

What Should We Be Looking For This Time Around?

So what makes agentic commerce different from the graveyard of failed retail tech? Five things need to align:

- The technology itself. We need to move beyond clunky text interfaces toward multimodal experiences with persistent memory – so your shopping sidekick remembers your preferences, goals, and routines across sessions. Agent-to-agent protocols need to let AI agents reliably.

- There is pain in the incumbent solution. Choice overload isn't a nice-to-have problem—it's paralyzing millions of shoppers. (I covered this in detail earlier this week.) Are these painful enough motivators to get people off retailer apps and websites and into LLMs?

- Distribution needs to be frictionless. Unlike Echo devices sitting on counters, these agents live on the phones we're already addicted to. Check.

- The economics. Retailers, consumers, and platforms need to feel like they are winning from a commercial standpoint. These are materializing now with ChatGPT's app store - Instacart, Uber, Doordash, and Target have announced early partnerships here.

- What's missing? Cultural readiness. Trust in algorithmic delegation isn't universal yet, particularly among older shoppers. But that's the one variable that shifts fastest once the experience works.

The Real Lesson Out Of Memphis

Clarence Saunders didn't wait for shoppers to request self-service. He saw inefficiencies everyone else tolerated and reimagined the entire system. The result looked irrational—until it became inevitable.

I'm not arguing that agentic commerce will kill ecommerce as we know it. I'm arguing that dismissing the possibility based on today's clunky implementations ignores how often "irrational" innovations found their moment once the surrounding technology matured.

The skeptics might be right. History is littered with technologies that never escaped the hype cycle. But history also shows us that some innovations start in a single store in Memphis, looking absurd to everyone who hasn't seen what's possible yet.

We're all speculating about a future none of us can predict with certainty. But given how often the "obviously irrational" became "obviously inevitable," I'd rather prepare for the possibility than assume current limitations reveal permanent constraints.

PS - Every RMN says they’re winning incremental media dollars. Every brand quietly admits they are re-allocating their trade spend. Who’s right?

Join me and the CEO of Pentaleap, Andreas Reiffen, for a lively livestream discussion about trade media versus retail media, next Thursday at 10:30AM ET on LinkedIn Live.

No slides. No over-prep. Just a smart, fast-moving conversation you won’t find on any conference stage.

We’ll unpack:

🔹 What Bain, Forrester, and brand leaders are saying about “the trade trap.”

🔹 Why U.S. vs. Europe sees this issue so differently.

🔹 How retailers could actually win incremental budgets (hint: it’s not another walled garden).

👉 Join us live on LinkedIn to ask your questions and shape the discussion in real-time.

And finally, here's more from me on this & related topics: